KS4 Lines and Angles Worksheets

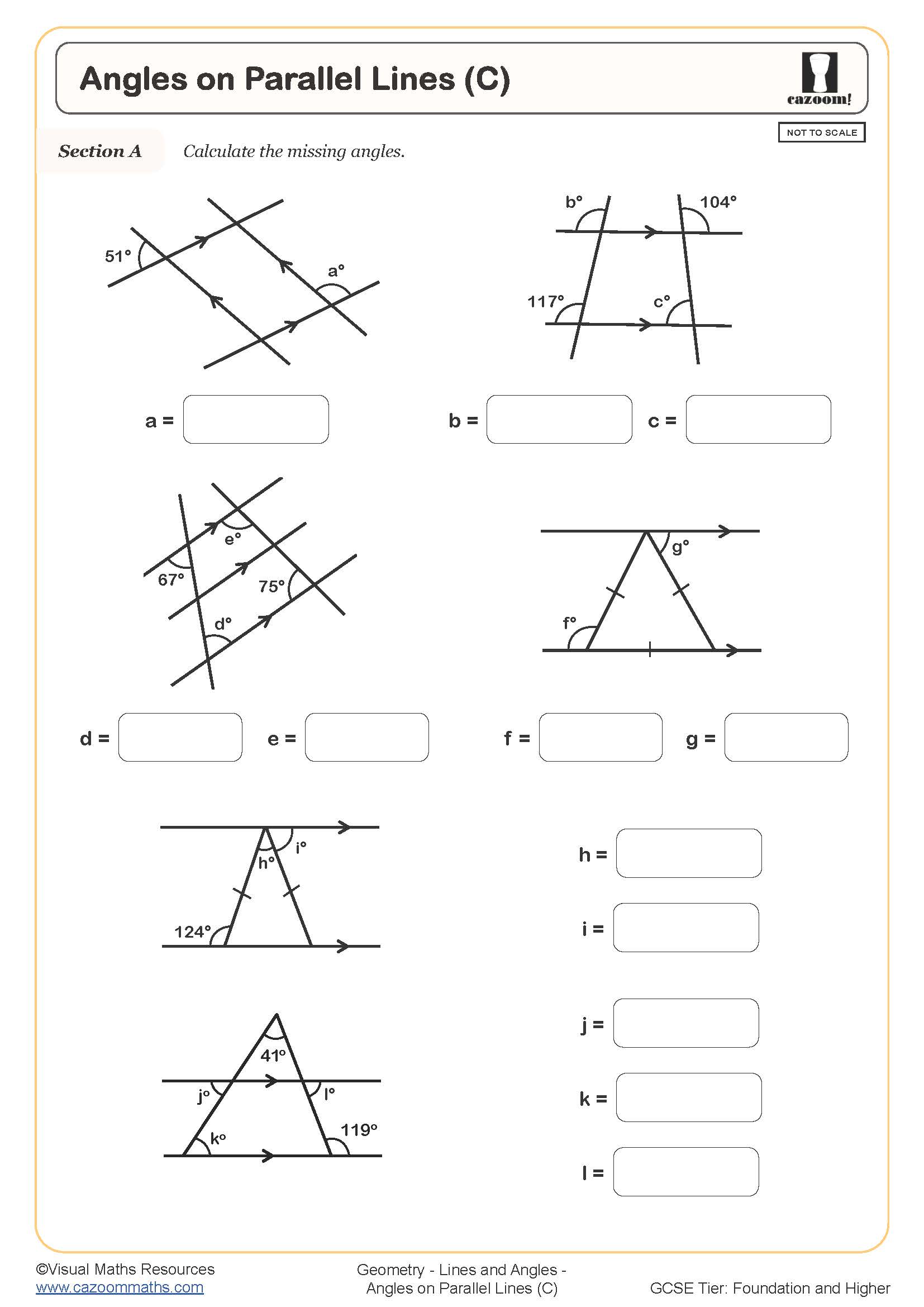

Angles on Parallel Lines (C)

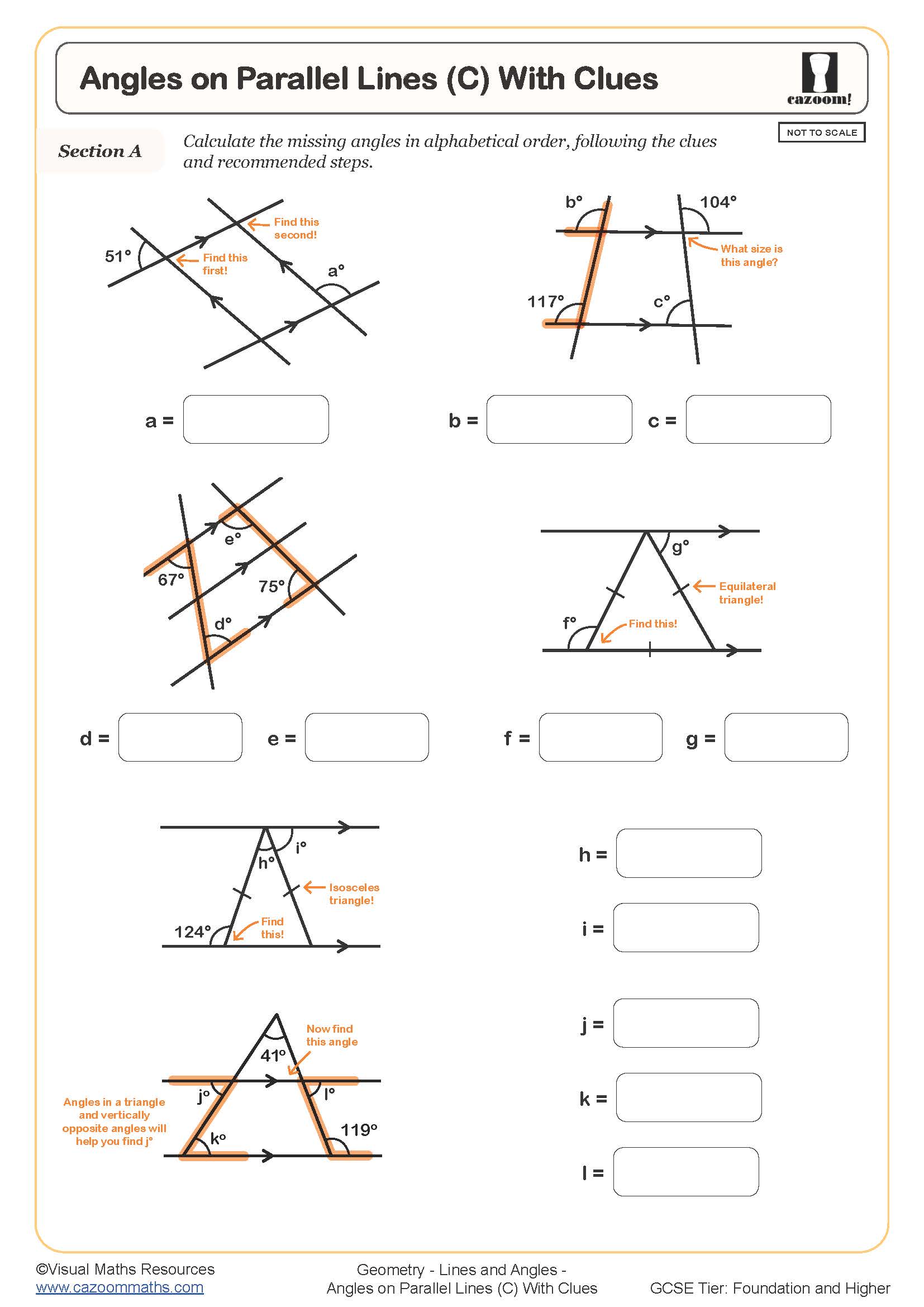

Angles on Parallel Lines (C) (With Clues)

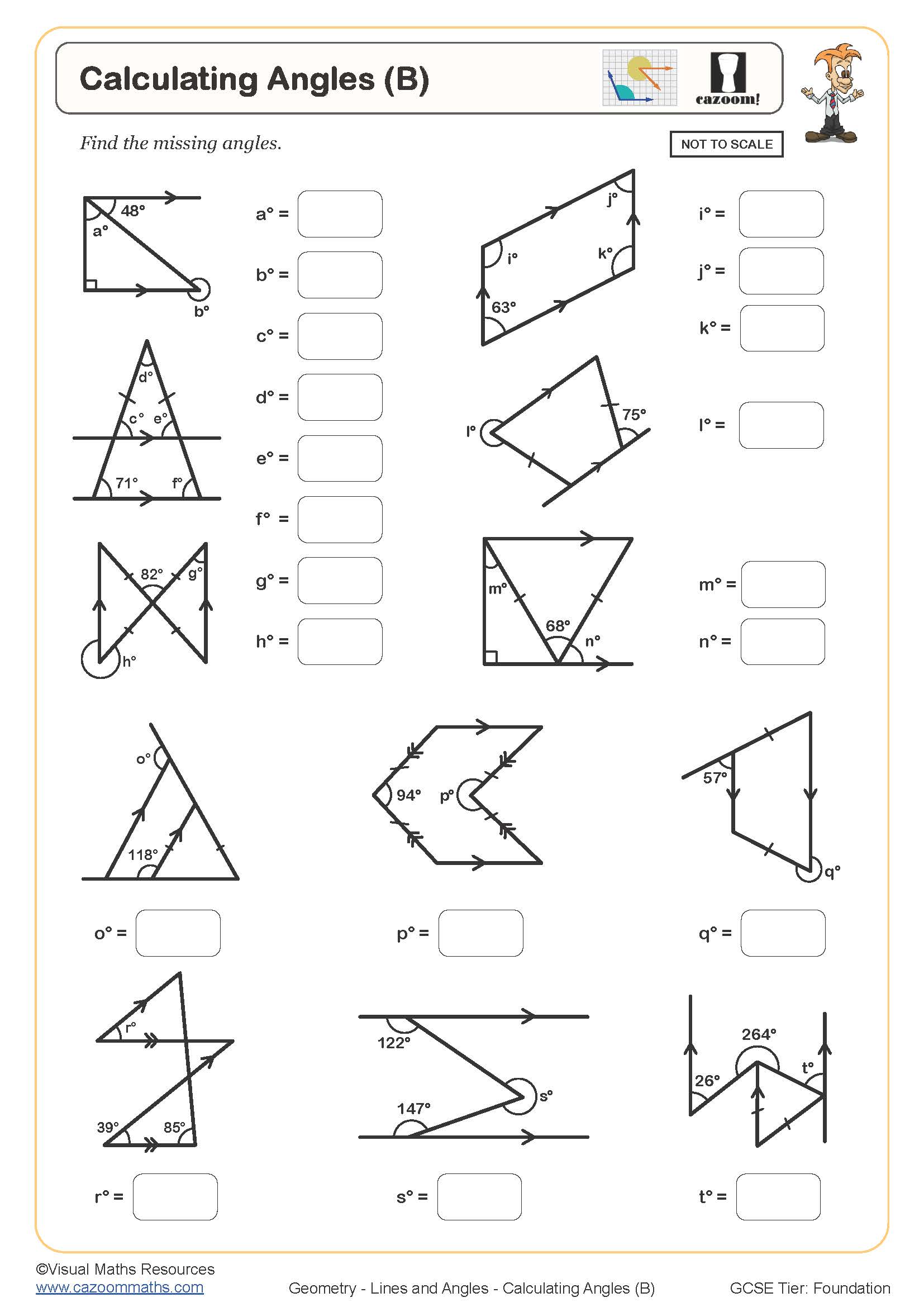

Calculating Angles (B)

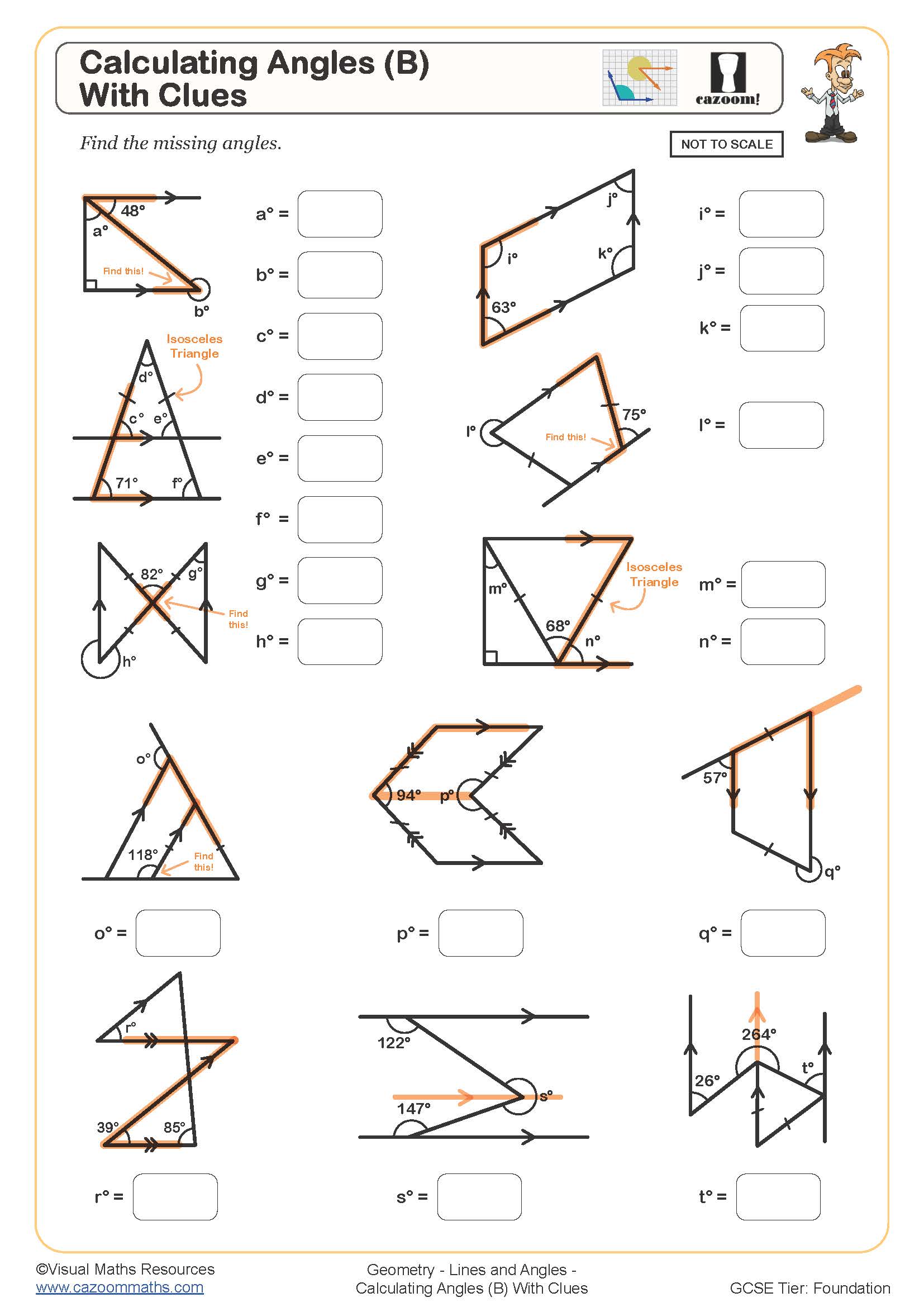

Calculating Angles (B) (With Clues)

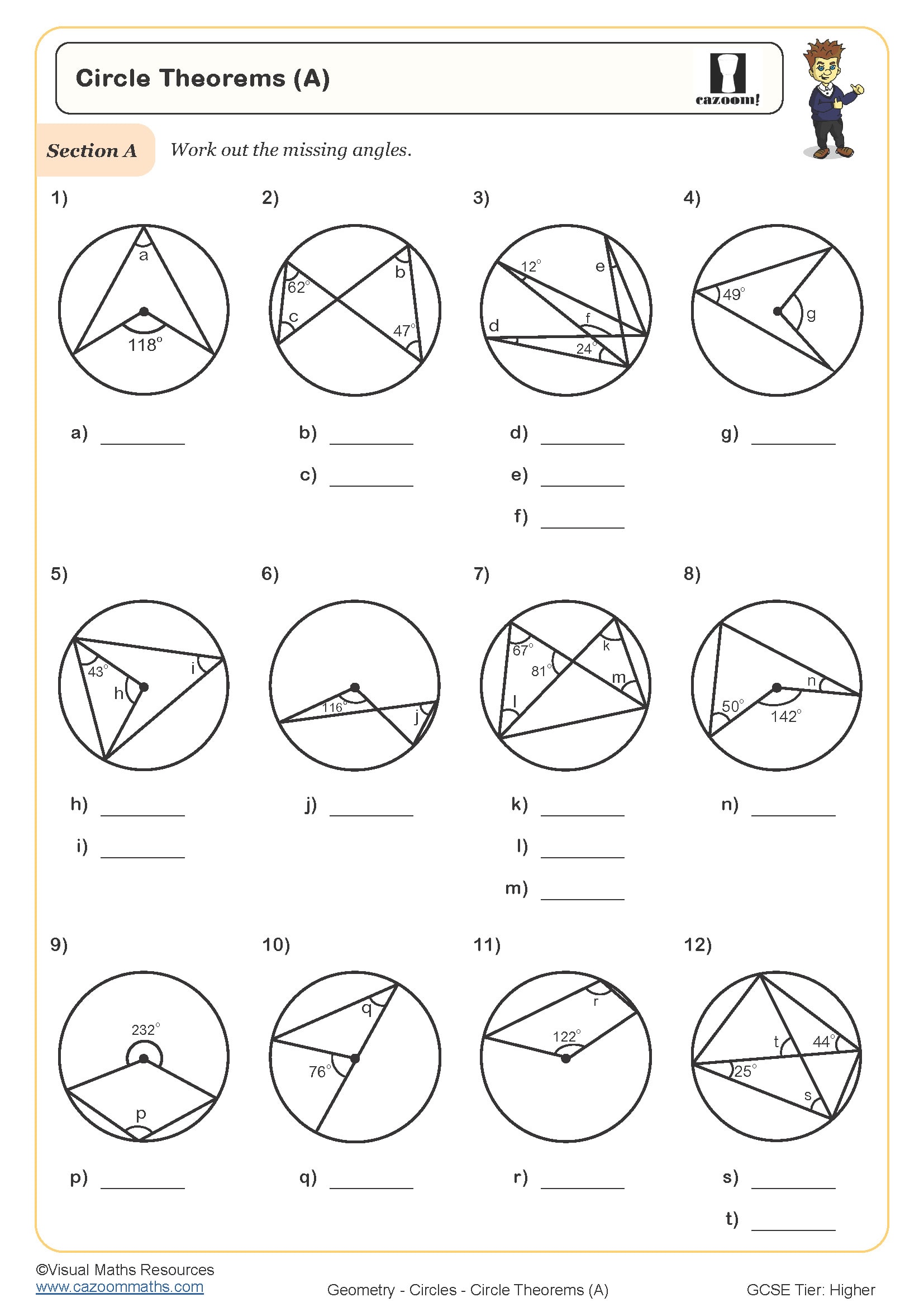

Circle Theorems (A)

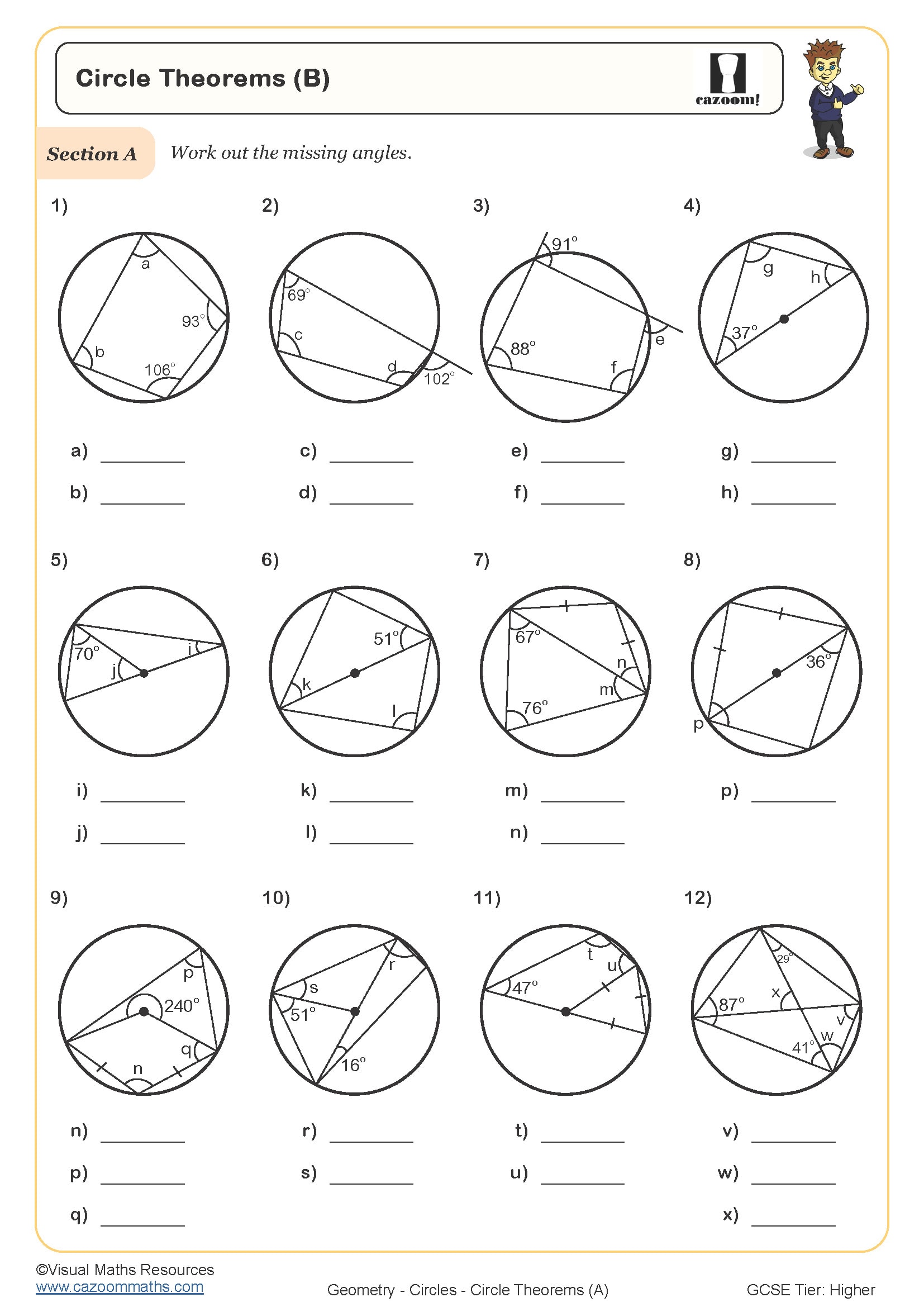

Circle Theorems (B)

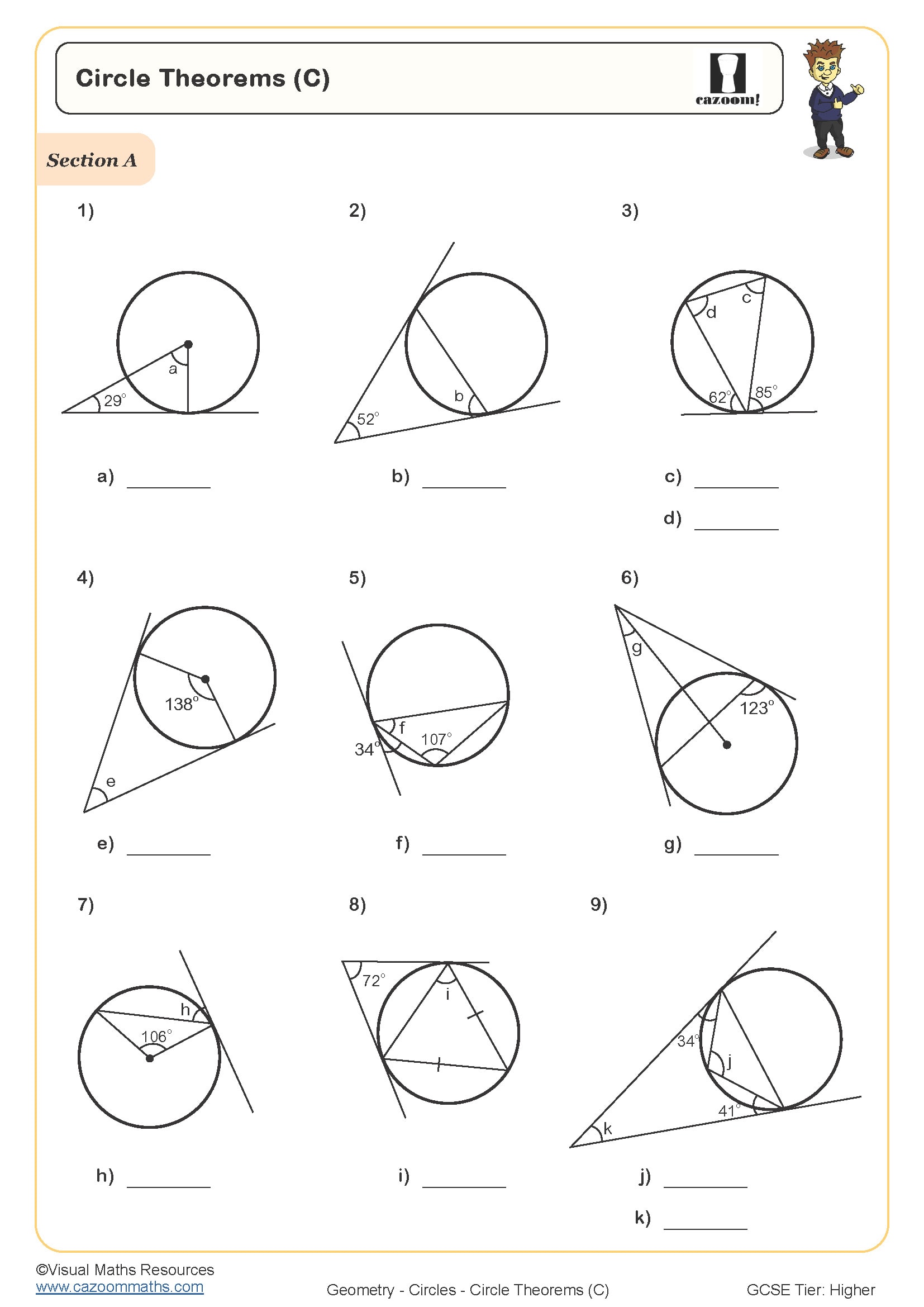

Circle Theorems (C)

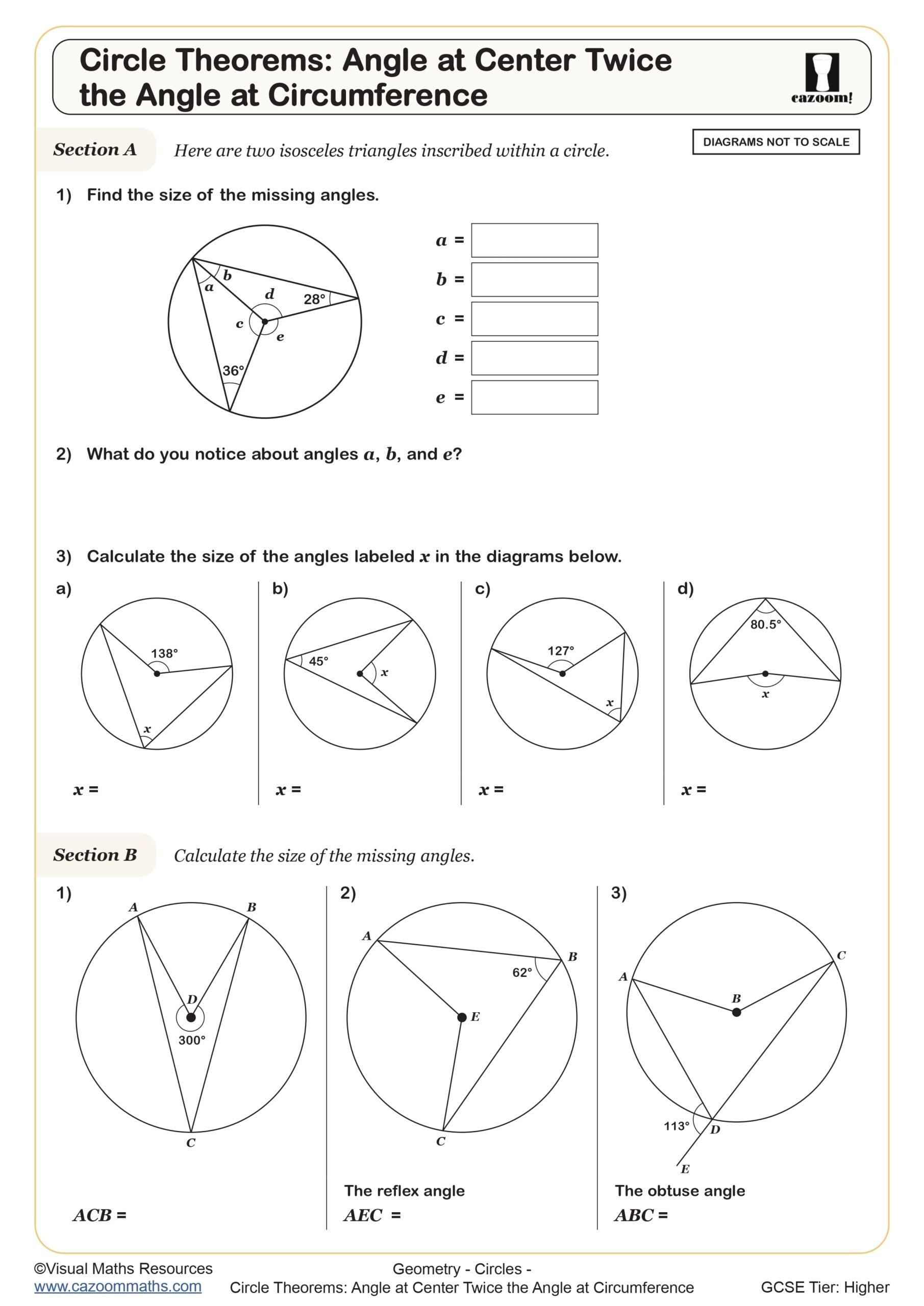

Circle Theorems: Angle at Center Twice the Angle at Circumference

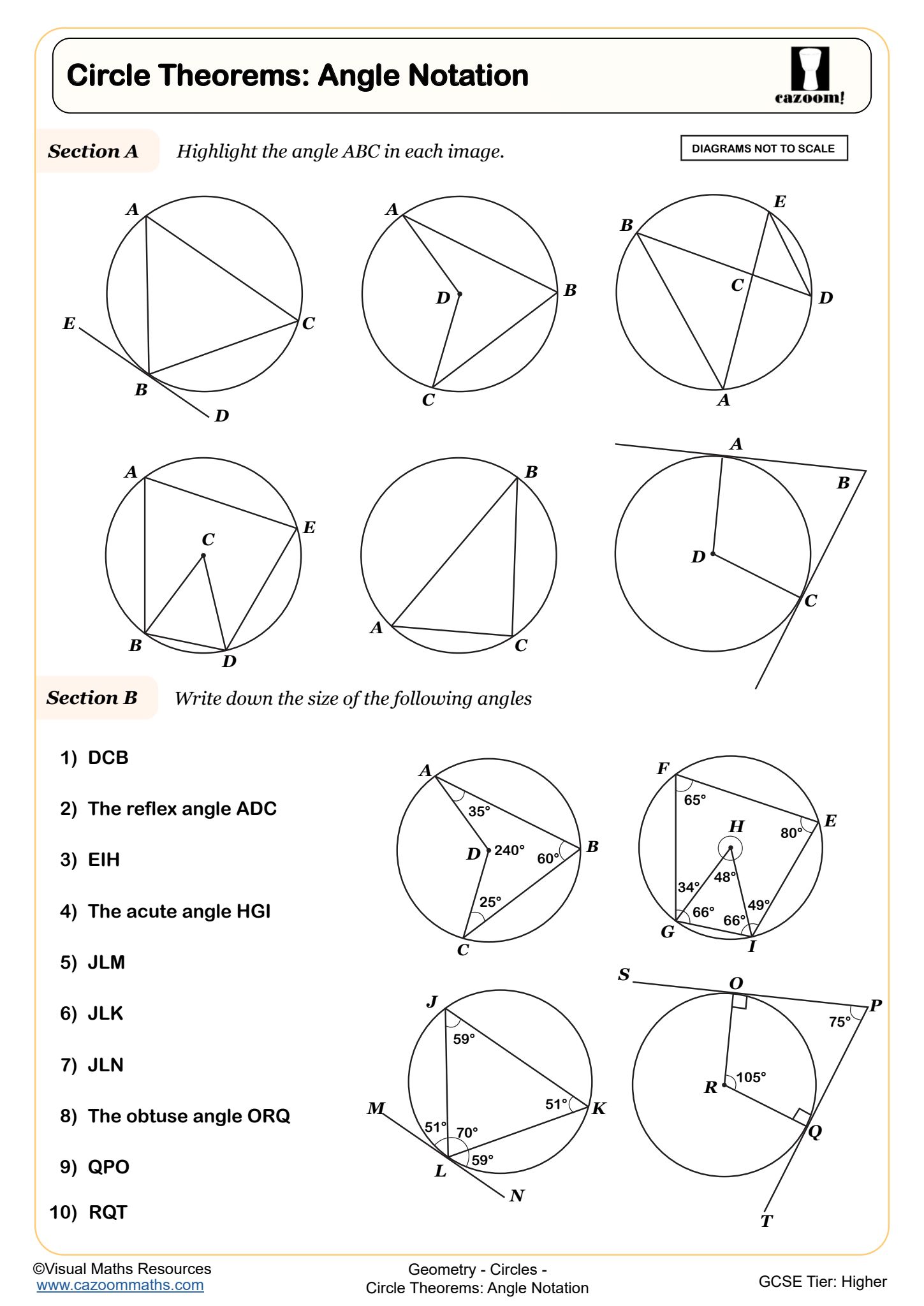

Circle Theorems: Angle Notation

Circle Theorems: Cyclic Quadrilaterals

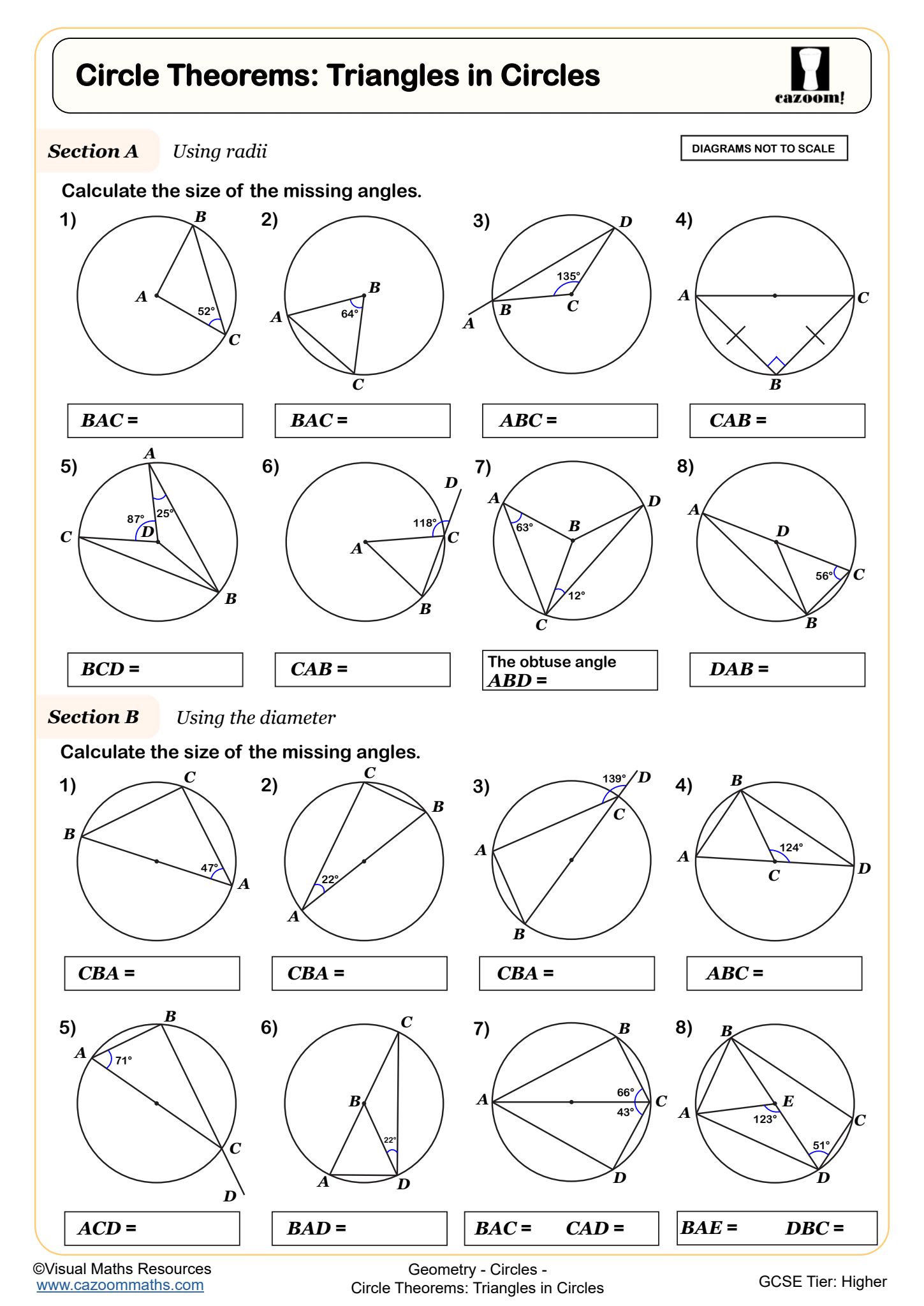

Circle Theorems: Triangles in Circles

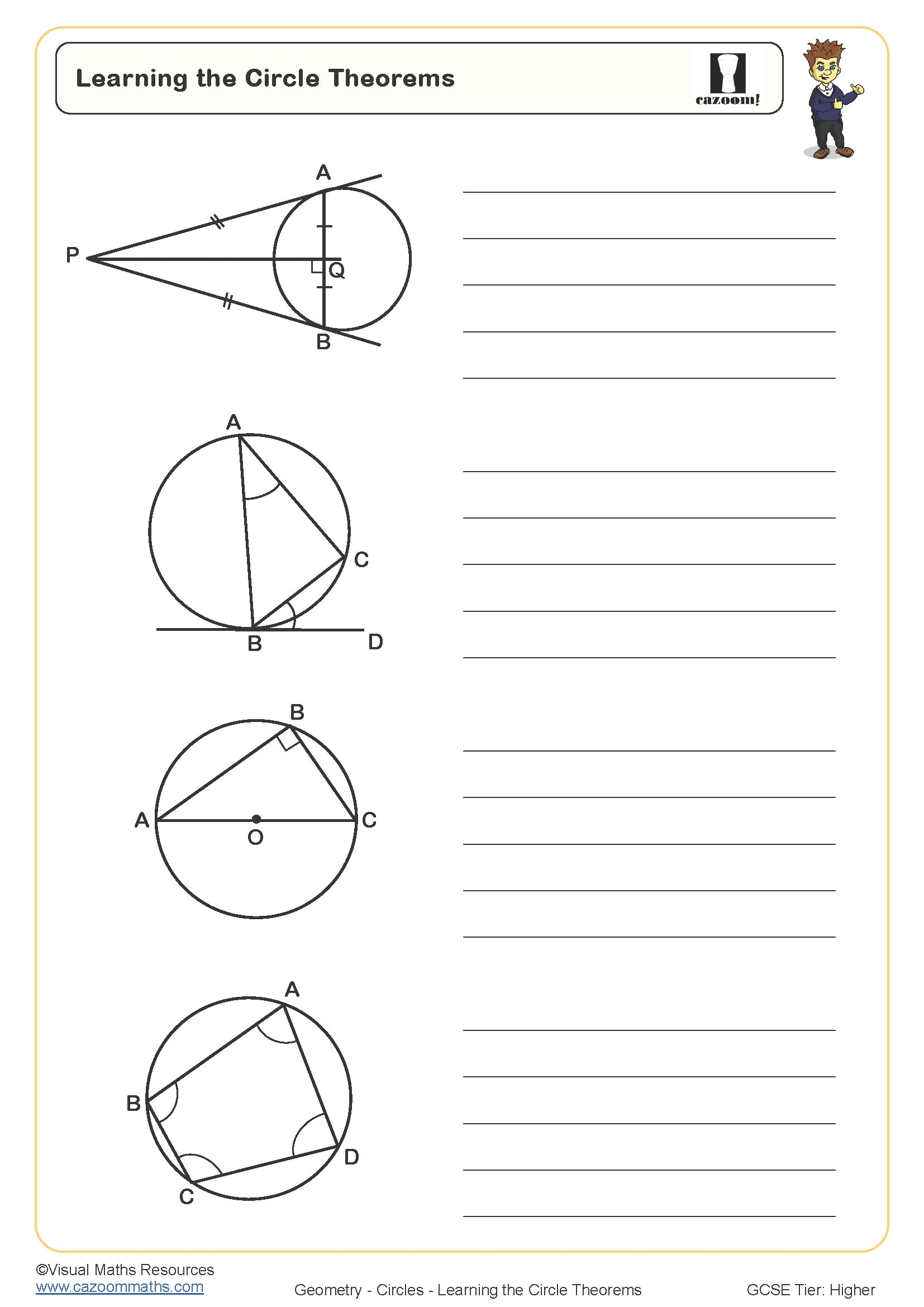

Learning the Circle Theorems

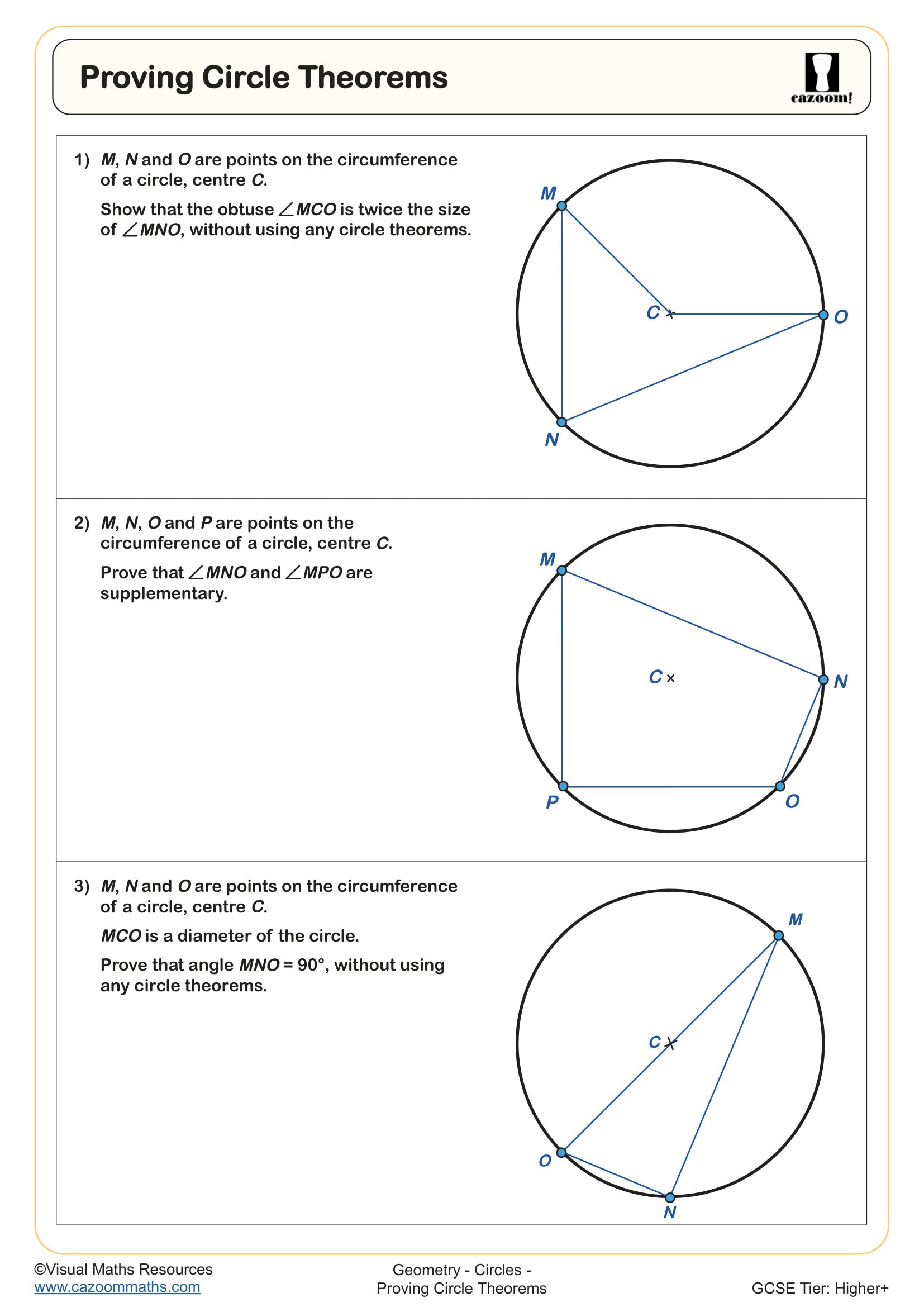

Proving Circle Theorems

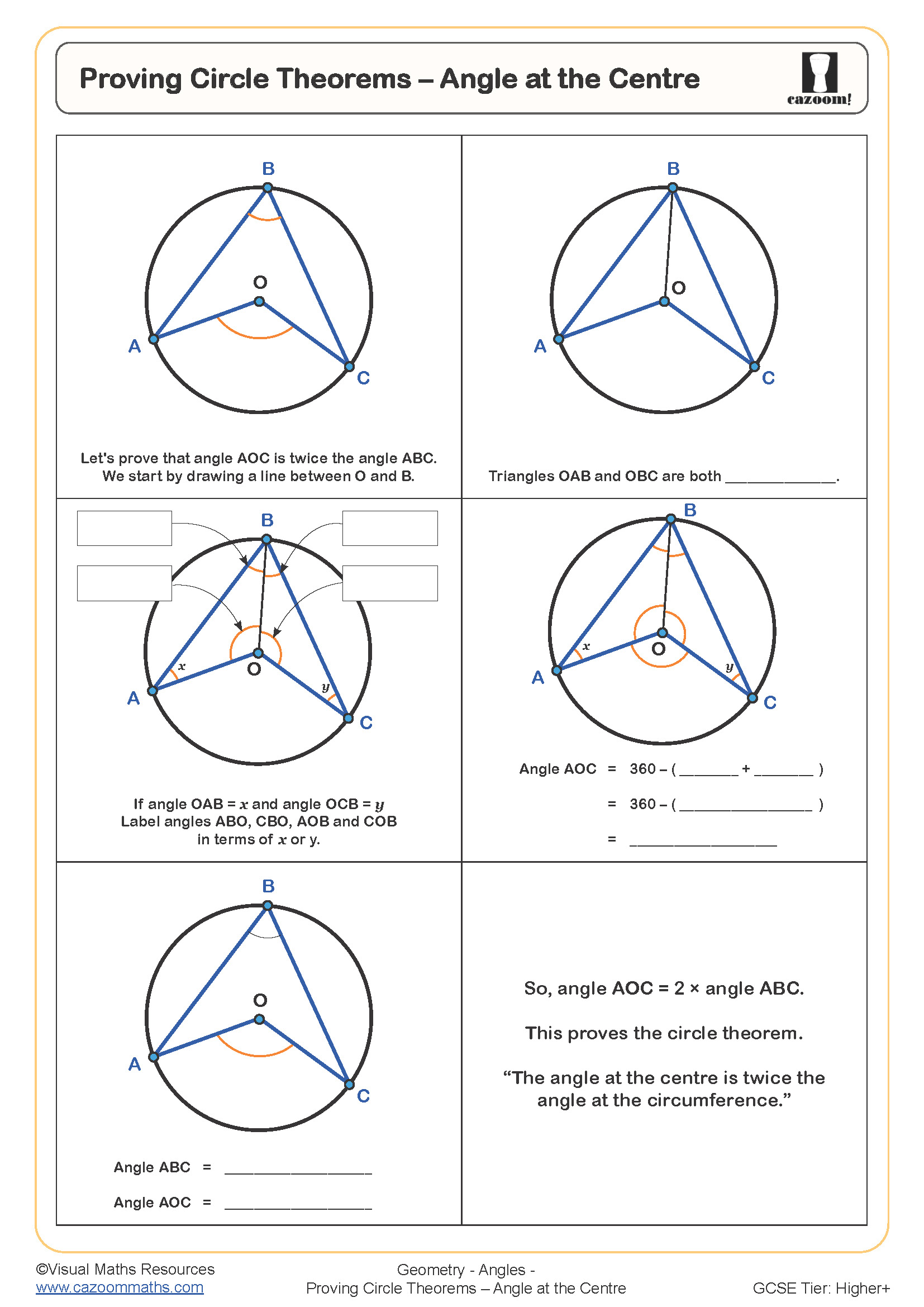

Proving Circle Theorems - Angle at the Centre

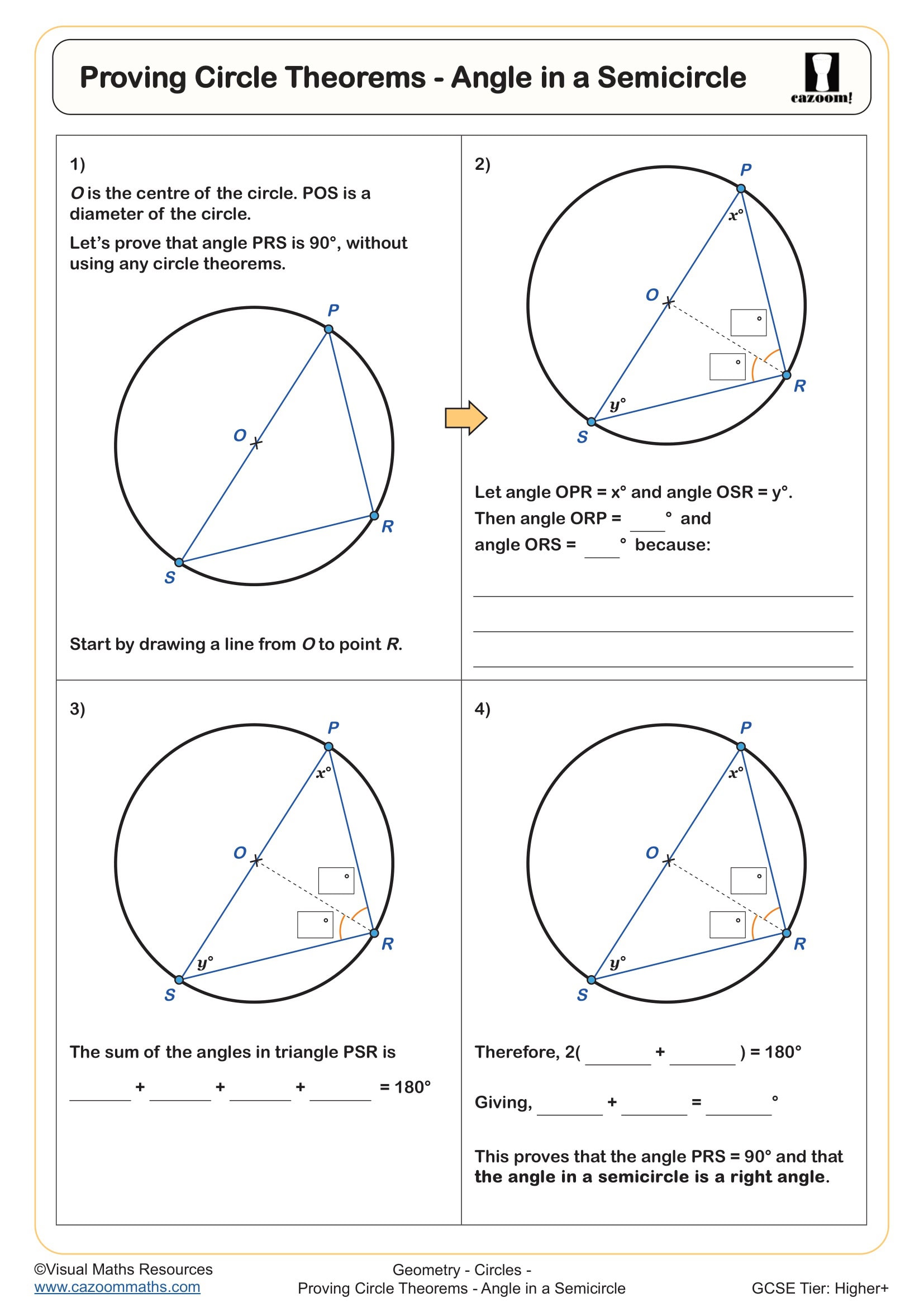

Proving Circle Theorems - Angle in a Semicircle

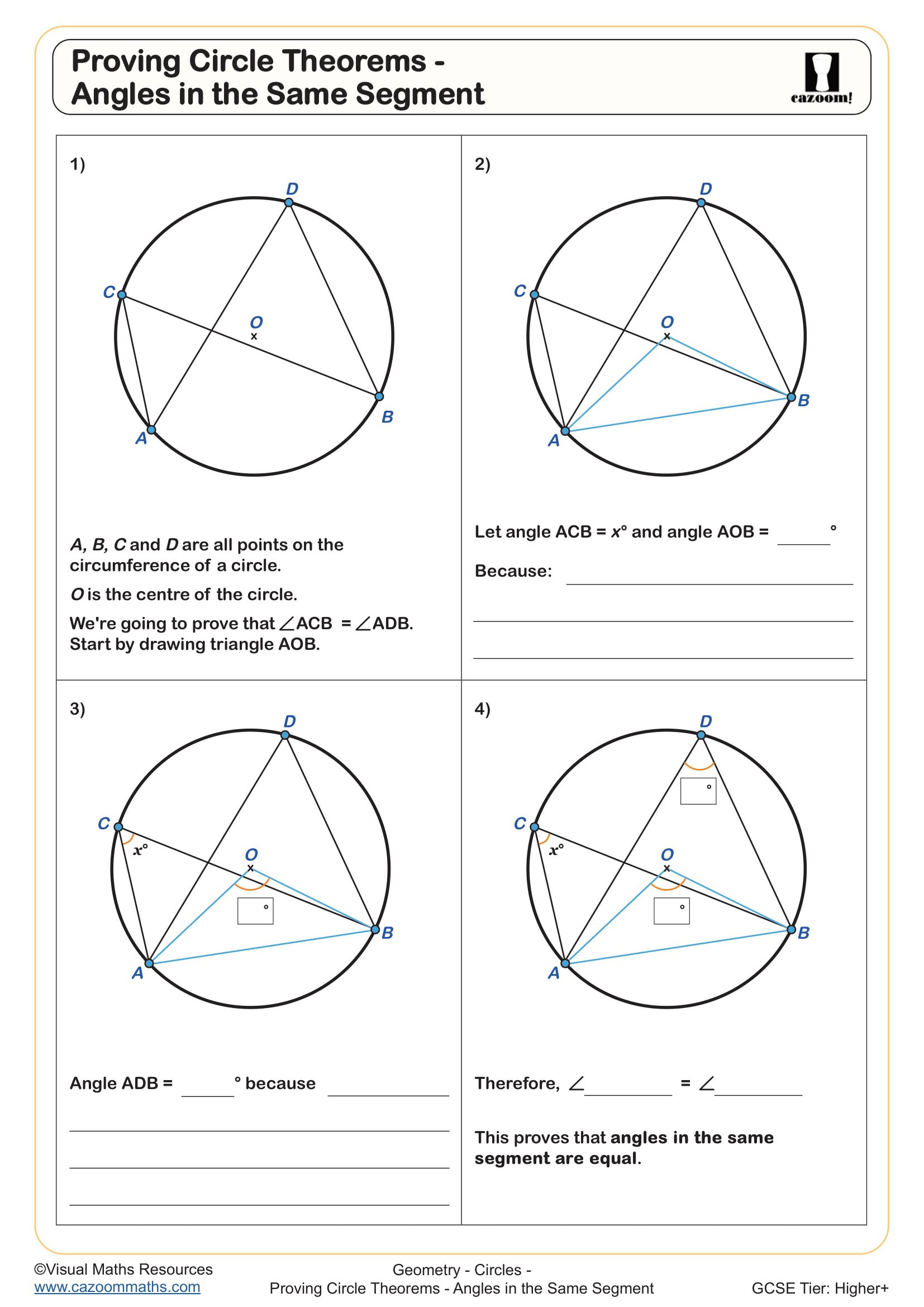

Proving Circle Theorems - Angles in the Same Segment

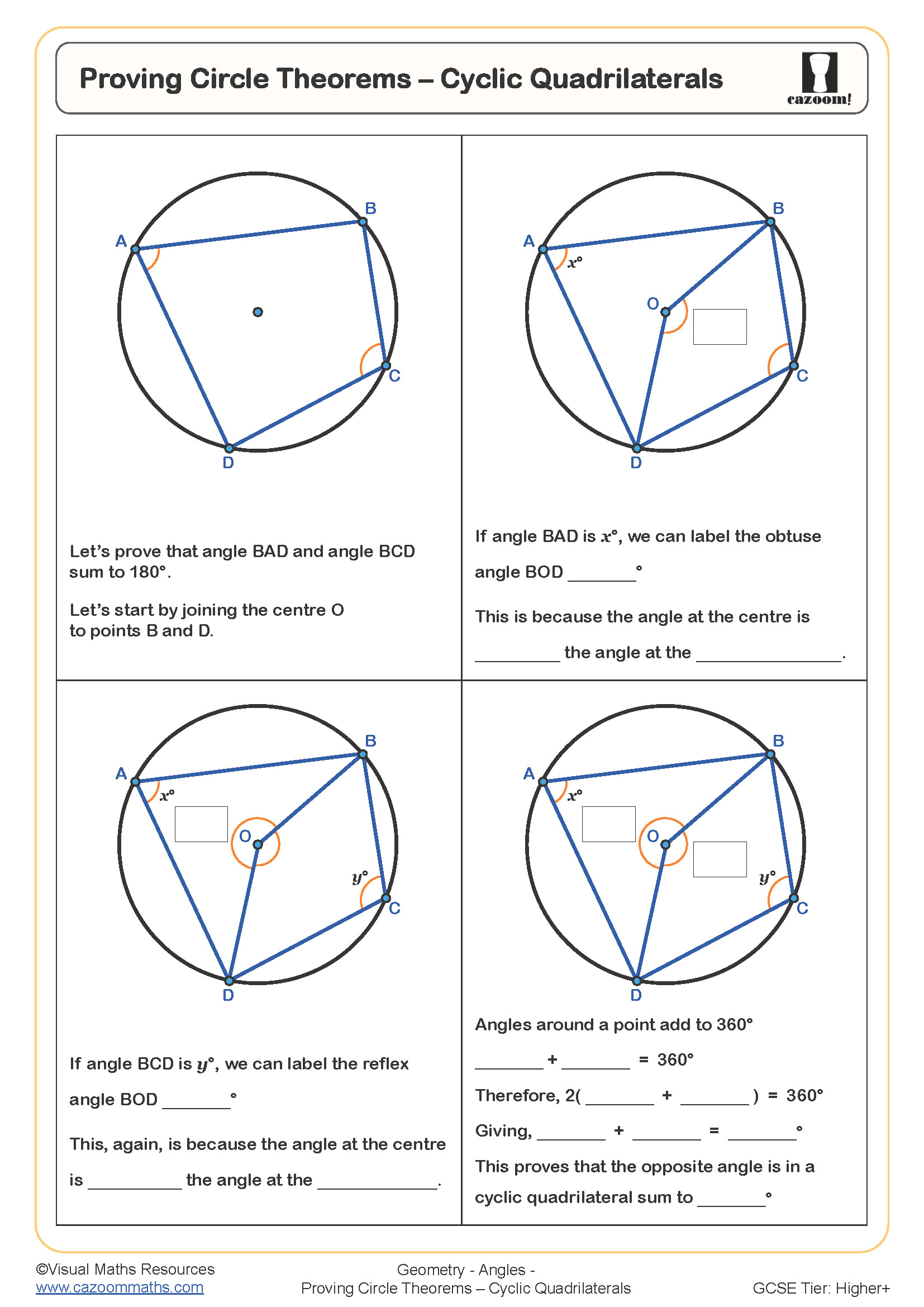

Proving Circle Theorems - Cyclic Quadrilaterals

What should a lines and angles worksheet include?

A well-designed lines and angles worksheet should cover angle properties at parallel lines (alternate, corresponding, and co-interior angles), angle facts in triangles and quadrilaterals, angles in polygons, and increasingly complex multi-step problems. At KS4, worksheets need to move beyond simple angle calculation to include algebraic expressions, equations formed from angle relationships, and formal geometric reasoning that reflects GCSE expectations.

Students lose marks when they state angle facts without proper justification. Exam mark schemes expect precise language such as 'alternate angles are equal' rather than vague statements like 'they're the same'. Teachers often find that students who practise identifying angle relationships on varied diagram orientations perform better under exam conditions, where diagrams deliberately avoid standard horizontal-vertical presentations.

Which year groups study lines and angles at KS4?

Lines and angles appears in both Year 10 and Year 11 as part of the GCSE Geometry and Measures strand. Year 10 typically covers foundational angle properties, calculations with parallel lines, and polygon angle sums, whilst Year 11 extends to more demanding problem-solving, multi-step reasoning, and formal geometric proof. This topic links directly to circle theorems and other advanced geometry studied later in Year 11.

The progression across these year groups involves increasing algebraic complexity and formal reasoning demands. Year 10 students work with numerical angles and simple expressions, whilst Year 11 students tackle equations formed from multiple angle relationships and construct formal proofs using correct geometric notation. Higher tier students also encounter challenging problems combining angle properties with circle theorems and trigonometry.

Why do students struggle with angles in parallel lines?

Students often confuse alternate, corresponding, and co-interior angles because they rely on visual pattern-spotting rather than understanding the underlying relationships. Alternate angles form a 'Z-shape', corresponding angles an 'F-shape', and co-interior angles a 'C-shape', but these mnemonics fail when diagrams are rotated. The key conceptual understanding is that parallel lines never meet, creating predictable angle relationships wherever a transversal crosses them.

This geometric reasoning appears throughout engineering and architecture, where parallel structural elements create consistent angle patterns. Roof trusses, bridge supports, and railway track layouts all rely on parallel line geometry. Computer graphics and game design use these angle properties to calculate perspective views and ensure architectural models render correctly, demonstrating how foundational geometric principles underpin digital design technology.

How do these worksheets support GCSE preparation?

The worksheets build systematically from identifying basic angle relationships to constructing multi-step solutions that mirror GCSE question structures. Each resource includes varied problem types—some requiring pure calculation, others demanding algebraic manipulation, and many combining several angle properties in a single question. The complete answer sheets show formal working and correct mathematical language, modelling the precision examiners expect.

Teachers typically use these resources for targeted intervention when students demonstrate gaps in geometric reasoning, or as homework following initial teaching to consolidate understanding. They work well in paired activities where students explain their reasoning to each other, addressing the common classroom observation that students can calculate angles but struggle to articulate why relationships exist. The scaffolded approach across the collection allows differentiation within mixed-ability groups.