Year 8 Factorising Worksheets

What is factorising in Year 8 maths?

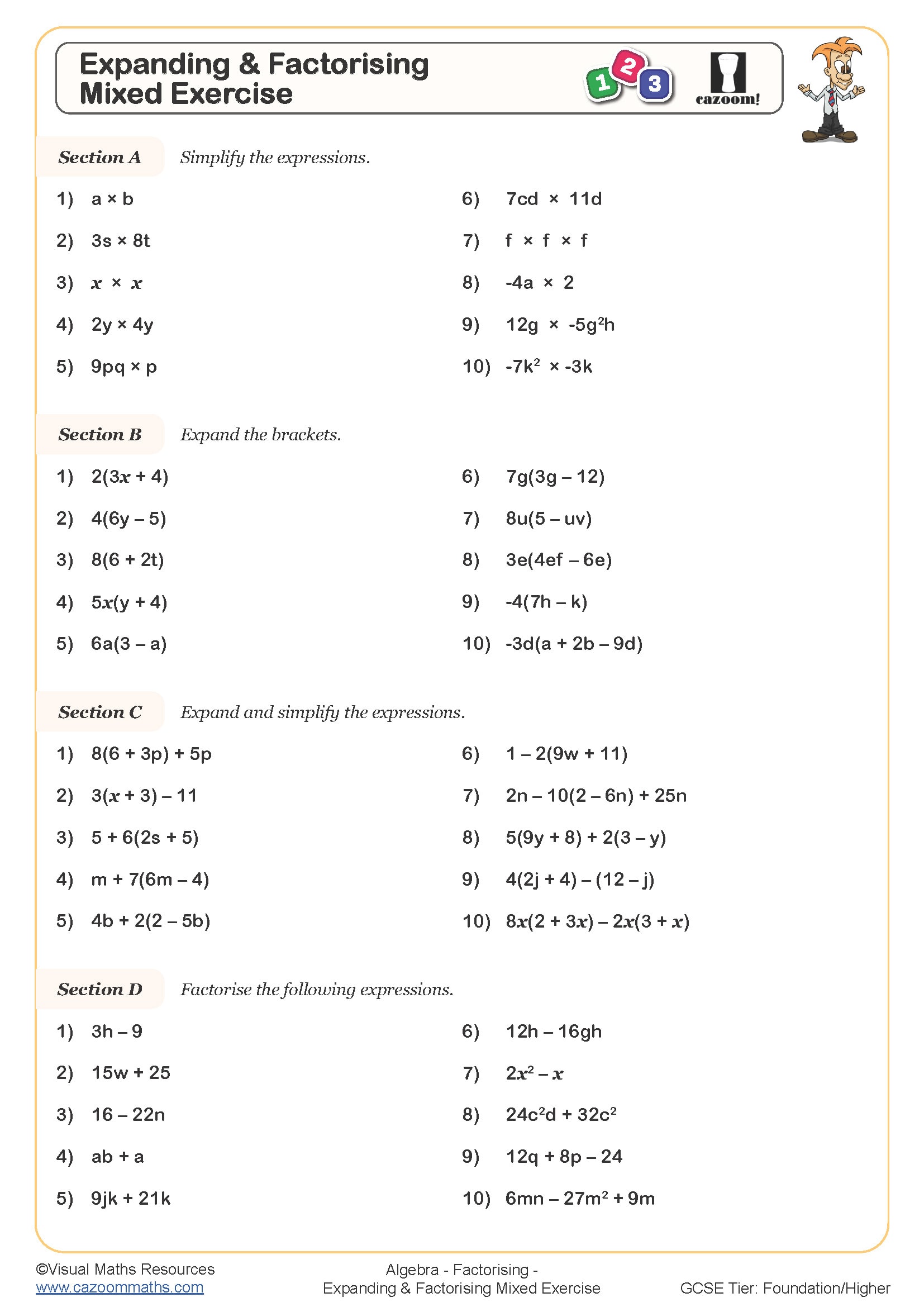

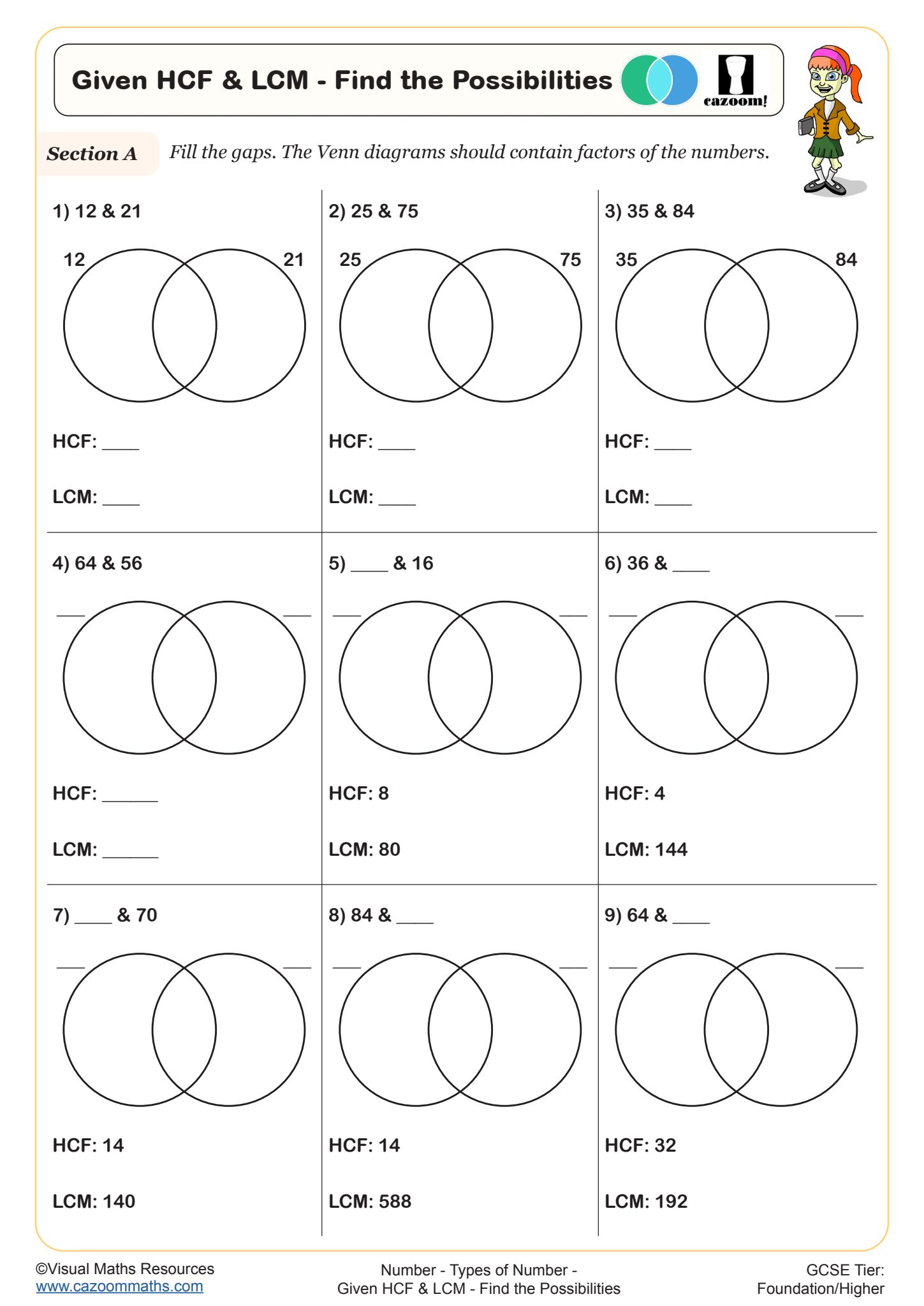

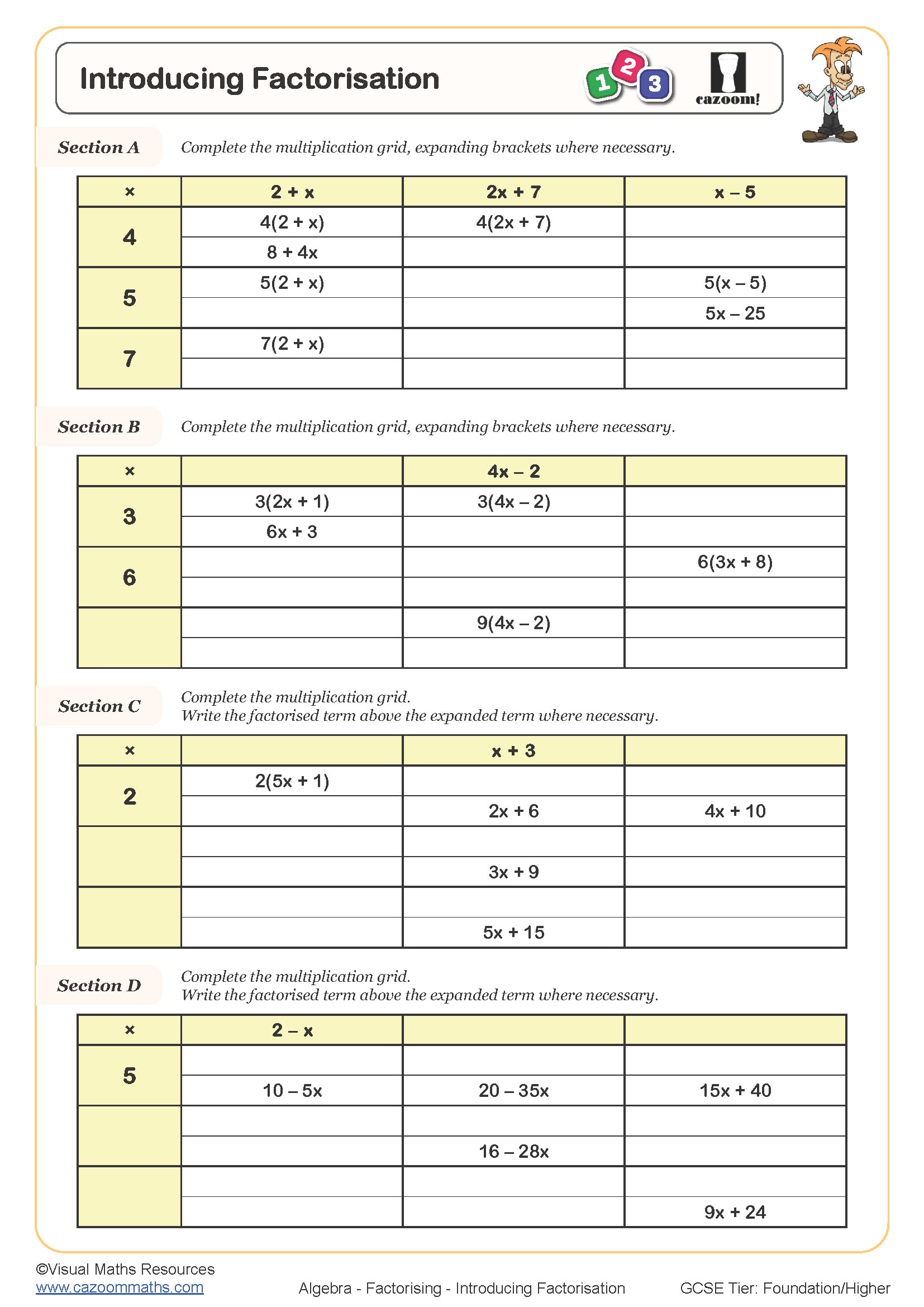

Factorising in Year 8 maths involves writing an algebraic expression as a product of its factors by identifying the highest common factor (HCF) of all terms. Students learn to recognise that 4x + 12 can be rewritten as 4(x + 3), extracting the common factor that appears in every term. This sits within the KS3 algebra strand of the National Curriculum and builds directly on simplification skills developed in Year 7.

A common error occurs when students identify only part of the HCF, writing 15x + 10 as 5(3x + 2) when they should extract the full HCF of 5. Mark schemes award marks for correctly identifying the HCF and for accurate terms inside the brackets, so both stages matter. Teachers often use the "reverse check" strategy, asking students to expand their factorised answer to verify it matches the original expression.

Which year groups learn factorising?

These worksheets are designed specifically for Year 8 students working within Key Stage 3, typically for pupils aged 12-13 who have already mastered basic algebraic manipulation. Factorising first appears formally in the KS3 curriculum after students have developed confidence with expanding brackets and collecting like terms, as they need to recognise the reverse process clearly.

The progression in Year 8 moves from simple single-term factors like 2(x + 5) through to expressions with multiple terms and larger coefficients such as 18xy + 12x. Students who struggle with times tables often find identifying numerical HCFs challenging, whilst those who rush may miss algebraic factors entirely. This groundwork becomes essential preparation for factorising quadratics in Year 9 and GCSE topics including solving equations and simplifying algebraic fractions.

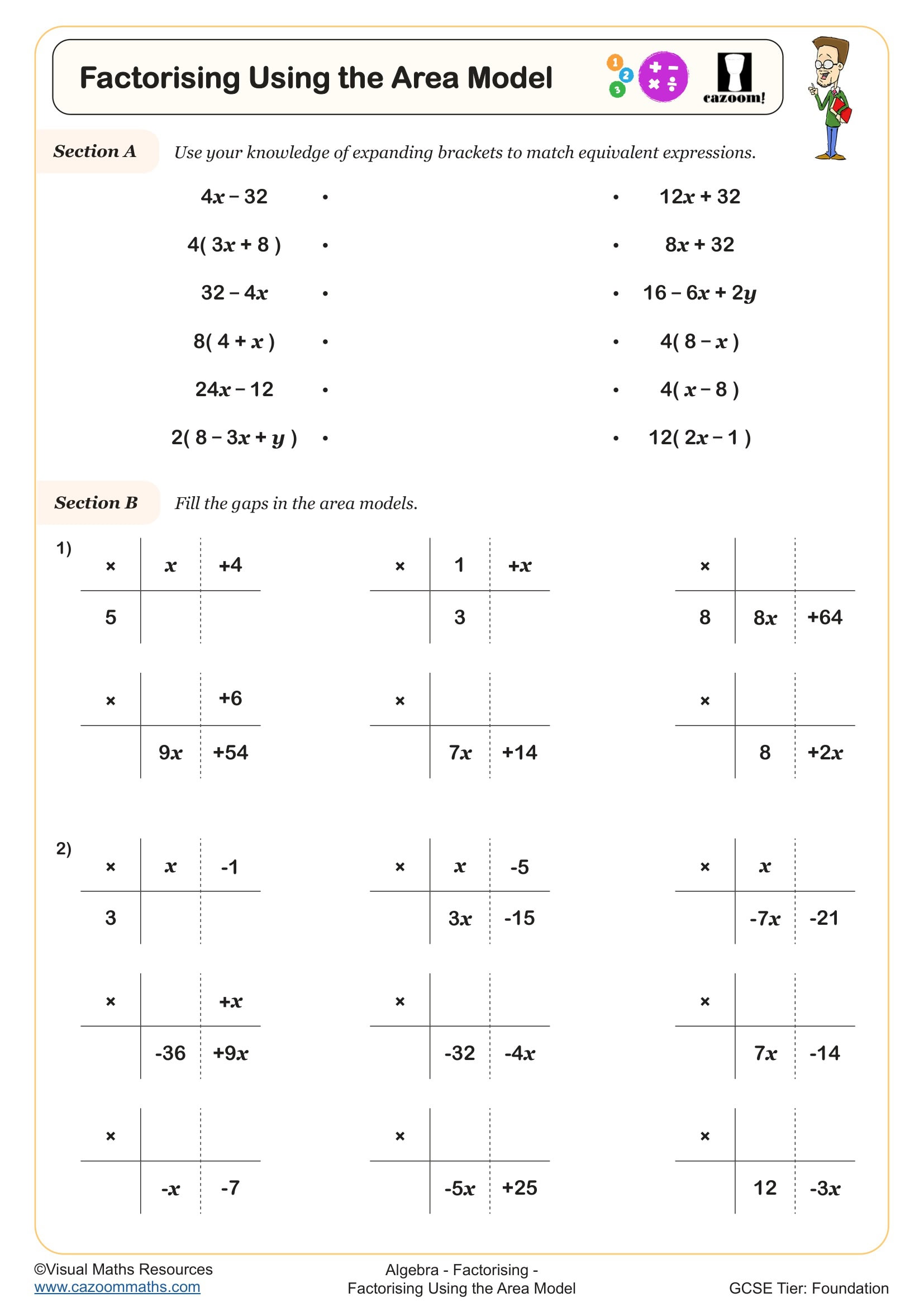

How does splitting down help with factorising?

Splitting down is a systematic approach where students break complex expressions into manageable parts before identifying common factors, particularly useful when dealing with expressions containing multiple variables or larger coefficients. Rather than attempting to factorise 24ab + 16a in one step, students learn to identify factors separately (24 = 8 × 3, 16 = 8 × 2, both contain 'a'), then combine this information to extract 8a(3b + 2). This methodical process reduces errors and builds confidence with increasingly complex algebraic terms.

Engineers and programmers regularly use factorising when optimising code or simplifying formulae in manufacturing processes. For instance, calculating material costs for rectangular items might involve expressions like 4lw + 2l, which factors to 2l(2w + 1), immediately revealing that length is a common factor affecting total cost. This skill of recognising common elements within complex systems transfers directly to problem-solving in physics, computing, and design contexts throughout STEM careers.

How can teachers use these factorising worksheets effectively?

The worksheets provide graduated practice that allows teachers to differentiate according to student confidence levels, with questions moving from straightforward single-variable expressions through to mixed terms requiring careful identification of both numerical and algebraic factors. Complete answer sheets enable students to self-mark during independent work, whilst teachers can use partially completed worksheets as worked examples on the board, asking students to identify errors deliberately planted in the factorisation process.

Many teachers use these resources for targeted intervention with small groups who struggled during initial teaching, as the clear structure helps students revisit misconceptions without feeling overwhelmed. The worksheets work well as homework tasks following classroom introduction, allowing students to consolidate methods at their own pace. For paired work, one student can factorise whilst their partner expands the answer to check accuracy, creating immediate feedback loops that strengthen understanding of the relationship between these inverse operations.